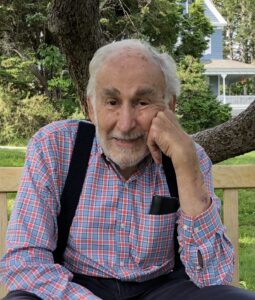

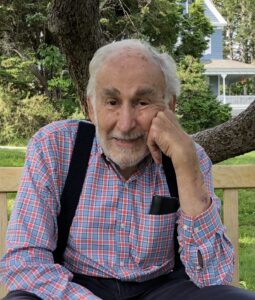

Remembering John Collins

Reverend John Arthur Collins died peacefully in his sleep at home in New Rochelle, NY onJanuary 27, 2025. Rev. Collins was born in Chicago

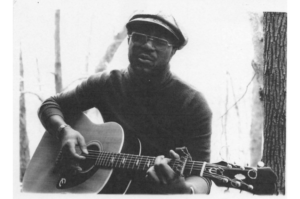

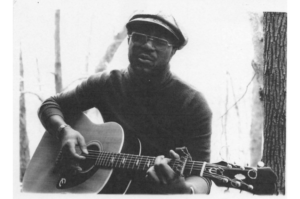

February 17th marks the anniversary of Dr. Jim Dunn’s transition to the village of the ancestors. Jim was the co-founder of The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, and before that, he organized in places such as Yellow Springs, Ohio and Des Moines, Iowa.

Dr. Jim Dunn’s dissertation was titled, A Whole Lotta Peoples Is Strong, and was submitted to Union Graduate School in May 1978, two years before the founding of PISAB.

In it, Dr. Jim Dunn recounts his foundation of community organizing in The Bottoms, a community in Des Moines, Iowa, in the 1960’s. He continues to reflect on the promises, successes, and missed opportunities of the Civil Rights Movement by traveling around the country to interview grassroots community organizers who were on the front lines of the movement.

His reflections on power, poverty, and community organizing are woven into the analysis of the Undoing Racism & Community Organizing and PISAB’s anti-racist organizing principles.

Please enjoy these excerpts from Dr. Jim Dunn’s dissertation. In his words, on learning to become a grassroots community organizers in Des Moines:

“Neither time nor space allow for details of the many events that all combined to serve as part of my growing pains. Suffice it to say, it was at this point in my life when I had a first-hand introduction to what grassroots community organizing and struggle were all about.

It was necessary from time to time to stand between two groups of kids and try to keep them from killing each other. Or to plead with a judge to not send a kid up. Or to sit long hours with crying mothers and try to give them a ray of hope. And it was important that I learn from those experiences. What I learned (it seems so obvious now) was that it is not enough to focus only on the visible problems. It was often even more important to be cognizant of the many forces that created and perpetuated the conditions that led to the problems. I found myself struggling for solutions.

I learned it was not enough to get a little baby girl into the hospital to be cured of

pneumonia, only to later discover that the house she returned to had no heat because the slum landlord refused to make such a provision. I could write a separate volume about the hours I spent trying to solve specific problems, only to find that when they seemed resolved they were

not. The forces creating them were untouched. It was a lesson that I guess all young organizers learn in one way or another.

I displayed even more naivete when I expected my agency to make the same discoveries and grow right along with me. As I stumbled around, still very much a child of community

organizing, bumping into obstacles I didn’t fully understand, I discovered a new word to be added to my vocabulary. That word was power.

The next obvious move was to understand who had the power and how it was maintained.”

After leaving the agency, Jim found himself organizing in the Southeast Bottoms – a historically poor neighborhood made invisible to most of the residents in Des Moines. 80% of people living in the Southeast Bottoms were without running water. Here, Jim writes about bringing community residents together:

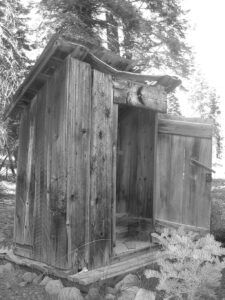

“…these things are now so basic to the American way of life that it seems only natural that one goes to a specified room inside the house to answer nature’s call. It’s only natural to walk into the kitchen for a glass of water when one’s throat is dry. Yet in the Southeast Bottoms in the mid-1960s the old days were still around. There was very little about them that could be considered good.

A young man or woman walking to the watering trough, jar in hand, or sitting in the outhouse, peering through the cracks at the men busy rebuilding the Dome on the Hill, or reading (they still read, but not Sears & Roebuck) their morning paper about the country’s latest ventures into space, knew that the world was passing them by. It was here where I first began to realize that poverty is a relative thing.

It was a short walk across the bridge or over the railroad tracks into downtown. There one could see the wealth glistening from the windows of all the fancy stores, or see fine folks dressed in fine clothes come out of big hotels and drive off in Cadillacs or a Mercedes Benz.

After returning home, clicking on the television (the modern Sears & Roebuck catalog) and seeing how comfortable the rest of the world lived, one could not help but think like the short gray-haired old man with the pot belly who said, “I’ve lived here for over 50 years and I’ve

seen a lot of change in this city, but not here in the Bottoms.”

As folks watched the world go by, what little ray of hope they had left became dimmer and dimmer. In many it flickered and went out completely. They had been told in myriad ways that only they were to blame for their lowly condition. Often the message was direct and blatant: You people must like living like that. I used to be poor and had an outhouse too. But look at me now.

Other times it took more subtle forms, like the Methodist Youth Fellowship coming in the spring armed with rakes and paint brushes to help those less fortunate creatures by cleaning up their neighborhood.

After so many years of bumping up against stone walls and enduring failure after failure, only to be told that their problem was due to a lack of self motivation, many people began to believe it. The 23 year-old woman I spoke with was right. The people’s spirits were broken. This was the real poverty. The kind one cannot see while taking a tour of the neighborhood.

I have only given a thumbnail sketch of the deplorable conditions under which the

Bottoms’ residents were forced to live. They seemed to have little trouble surviving all of that. There’s something about human nature that enabled them (and me later) to live with the outhouses, unpaved streets, the water trough, and run-down homes. What they could not cope with was the feeling of being less than human…

Meanwhile, the Improvement Council continued holding their weekly meetings, claiming to represent the people. They were never able to understand that in the face of all this stacked

up pain and misery, putting asphalt around their little water hole just added insult to injury. Rakes and springtime paint brushes could never serve to jar them out of the apathy in which they had been forced to reside.

Our challenge was not an easy one. How could we present a different vision than those who had gone before us? What was needed to fan that dim light that remained in those few who had not yet totally abandoned hope? How were we to reignite it in the many who had? We knew we had to be where the people were. So we went to church, the barber shop, laundromat, local bars, and wherever else we could find folks. Sometimes we would follow them home and spend long hours talking and listening.

Numerous concerns were expressed. The one that invariably recurred, however, was the need for sewers in the area. After we convinced enough people that the lack of sewers was not their fault and that it really wouldn’t help to get Mrs. Johnson to clean up her yard, we called for a neighborhood meeting.

Anyone who has done grassroots organizing knows how those first meetings go. Even though most of the time was taken up by individual complaints, it was clear that most of the people were there because they were fed up and angry. They wanted to do something. Knowing I was taking a risk, I explained how Blacks in the south and poor people all over were beginning to be heard only because they had taken to the streets. They had decided to no longer remain quiet and accepting of their plight.

I was prepared to hear them denounce us as subversive radicals when I suggested a demonstration. The room that had been buzzing with voices, some louder than others so they could get in their point, was suddenly quiet. After what seemed like a long time, a man who was one of the ‘solid folk’ in the community spoke up.

“I think these young people are right. You know, it’s only the wheel that squeaks that gets the grease.” It was the first time I had heard that expression. I remember feeling warm inside as a big smile swelled up.

None of them had demonstrated before and we were bombarded by questions.

“Where are we gonna march to?”

“There ain’t gonna be no trouble now, is there?”

“How many people are going to march? Gotta be more than what’s in this room if we’re

going to be effective.”

“We’ll try to get more people,” I responded, “But the sit-in movement started with only four students sitting in at a lunch counter, and one woman refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus led to a major bus boycott.”

Finally it was decided. We would get as many people as possible and march to the state capitol building. We chose that site because our plight needed to be dramatized, and that building with its gold dome was a powerful visible reminder of the constant contrast between poverty and affluence.

On the appointed day we marched. Those too old or too ill to make the uphill trek

followed in cars. We sang freedom songs and accepted the hisses, the boos, and confused looks from people once we reached the downtown area. The TV cameras and newspapers were all there. Reporters came from as far away as Omaha, Nebraska to see what may have been a first in Des Moines. There was no doubt that it was a first for the Bottoms.

I would like to just say a word about what happened that day. Residents made speeches and songs were sung. A group went inside the building announcing they were going to use the bathroom. When they returned, the crowd that remained outside was cheering. One man said to a TV reporter, “I just wanted to see what it would be like to use a nice clean toilet.”

People who for years had complained to each other in their own little world were now making their plight public. It was the mid-1960s and all over the country there were sit-ins, lie- ins, swim-ins, kneel-ins etc. Some people who chose to be graphic described our action as a “shit-in.” The polite reporter from Omaha called it “operation headstop.” Whatever euphemism was used, the fact was that the Southeast Bottoms of Des Moines was no longer hidden. It had suddenly and dramatically become visible.”

Reverend John Arthur Collins died peacefully in his sleep at home in New Rochelle, NY onJanuary 27, 2025. Rev. Collins was born in Chicago

As we all navigate this current moment, we take strength in the commitment of anti-racist organizers from around the country. Recently, an organizer shared testimonials

February 17th marks the anniversary of Dr. Jim Dunn’s transition to the village of the ancestors. Jim was the co-founder of The People’s Institute for